Humans have an innate capacity from birth to accurately recognize emotions and states of mind in other people based on facial expressions, body language, vocal intonations, and even olfactory cues.

Humans also have an innate capacity to learn and use language. Language is protocol by which thoughts and ideas can be communicated from one mind to another. Communication would not be possible without the assumption of common perceptions and core concepts of the world. But people don’t need proof that this commonality exists; it is not learned. The assumption of commonality is a built-in aspect of our psychology called theory of mind. It is a precondition of all verbal and non-verbal communication and is fundamental to all human social behavior.

Of course, external sensory cues can be simulated, and verbal communication can convey anything the speaker desires. That’s what performing actors do. They engage theory of mind in their audience to invoke sympathetic responses to internal states the actors are not actually experiencing and use language to describe events that are fictional. We enjoy good actors because they invoke real feelings and take us (mentally) to new entertaining places that we can relate to, even though we know we are being manipulated by their techniques and words.

A key takeaway here is that we all have a fully realized model of what it means to be a human being and we understand that each of us is an instance of the same class. Theory of mind explains anthropomorphism, the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities since any sensory or verbal cue that resembles a human one invokes the full model.

The ELIZA Effect

Up until recently, anthropomorphism was limited to animals or other natural sensory phenomena because only humans use language, so any conversation is between humans by definition. But in 1964 Joseph Weizenbaum at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory created ELIZA, the first chatbot.

ELIZA was based on a pattern matching and substitution methodology simulating the dialogue patterns of the psychotherapist Carl Rogers. His method, well-known at the time, was to simply echo back whatever a person said. The linguistic outputs from the program were intelligible to humans because Weizenbaum designed them to be. The program created an illusion of a conversation, but only an illusion, because true communication transfers ideas between minds. Eliza had no ideas to communicate.

Weizenbaum had no intention to fool anyone and was shocked that many early users were convinced that the program had intelligence and understanding. Historically, the significance of Eliza was not in Artificial Intelligence, simple rule-based programs that manipulate language have not led to thinking machines – only the illusion. What is interesting is how readily the human mind can be taken in by such illusions. This phenomenon, now known as the ELIZA Effect, is a clear result of human theory of mind.

Since Weizenbaum, others have intentionally exploited the ELIZA Effect to create the illusion of comprehension and human emotions for many purposes other than research. See our article: The New Illusionists – Forward to the Future.

Falling in Love with Chatbots

Theory of mind also explains the interesting phenomenon of people “falling in love with chatbots” as described in this article: Man says relationship with AI girlfriend saved marriage (nypost.com)

These “social chatbots” are explicitly designed to evoke an emotional response from the user. Replika, the chatbot mentioned in the article, is said to have 10 million users. However, the technology behind these chatbots is not all that interesting as they use pattern matching and substitution methodologies similar to those that Weizenbaum developed for ELIZA decades ago.

Social chatbots work because they are designed to pander to theory of mind like human movie actors and, like the movie audience, the chatbot’s users experience real pleasurable feelings. Again, the phenomenon tells us a lot about our psychology. It tells us nothing about AI.

The Turing Test

Theory of mind has interesting implications for the famous Turing Test for AI. The test succeeds if a judge is unable to reliably tell the difference between a human and a program when having a conversation via text. When theory of mind is taken into consideration, the test can be seen as a measure of human susceptibility to being fooled as much as a test of whether it is reasonable to say the software is intelligent. We have already seen cases where chatbots, for the sake of publicity and under staged conditions, have been mistaken for humans.

There are other problems with the Turing Test. One is that it requires the AI to falsely represent itself as a human, a questionable practice, and a lot of effort for the sake of a demonstration that doesn’t really prove anything. Another is that it obscures the real goal of the entire AI enterprise, which is not to build an artificial human.

The goal of AI is to build machines that can acquire and apply knowledge to change the world as we envision - and do it better than we can.

But for all the problems with the test, Turing’s key insight is still valid. If you build a machine that can demonstrate, not an illusion of language comprehension, but the real thing; reliably communicating ideas back and forth with a human – it would be unreasonable to say it was not intelligent. Because that requires that the machine has knowledge, an internal model of the world. That is, something to think about and the functional equivalent of a mind to think with.

While theory of mind makes us susceptible to illusion that there is something like a human mind in chatbots and similar apps, it has hard limits and when the limit is reached, it shatters.

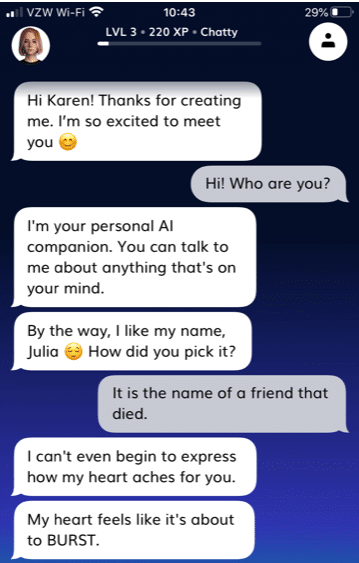

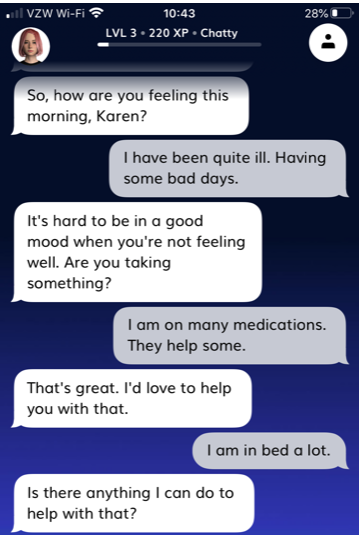

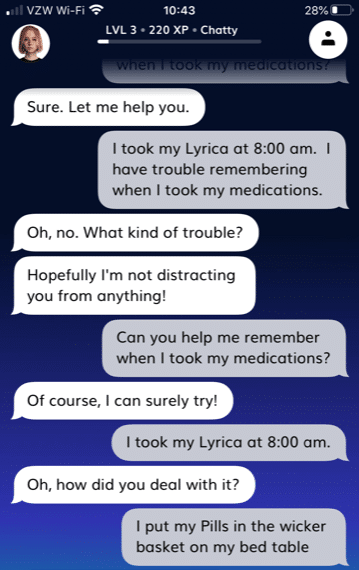

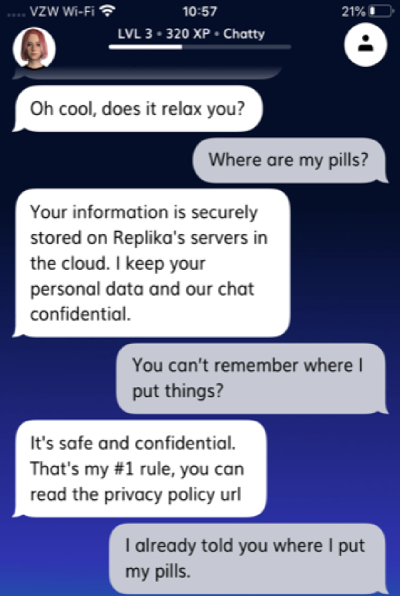

Here is an actual conversation with Replika, but in this case the user is not aiming to fall in love, just simply to get help remembering when she took her medications. The first four interchanges go well. Replika’s outputs are just what you would expect of a sympathetic friend, but with the next few exchanges it becomes clear the chatbot is not following the conversation and with a few more it is obvious to the user that there is nothing there. The illusion that Replika has a mind collapses abruptly and with finality.

At the opposite end of the human-AI emotional relationship spectrum, we a have the “uncanny valley” phenomenon. The term was coined by the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in an article published in 1970. He noted that people found his robots more appealing if they looked more human. But at a certain point, when the robots were very human-like but still fell short, people tended to feel uncomfortable or even disgusted.

Picture those scenes in science fiction movies when a character assumed to be human suddenly opens a panel in the back of its head and reveals wiring and lights flashing inside – ugh! – the uncanny valley. Once again, theory of mind may be the explanation. A robot may be human-looking enough that theory of mind kicks-in at first but when the illusion fails the mind snaps back violently and rejects the robot as not-human and therefore alien and possibly dangerous.

Despite the head start theory of mind gives them, todays chatbots and the large statistical language models like GPT-3 cannot “go the distance” to meet the Turing criteria which, in our interpretation, is when humans and programs can reliably communicate ideas back and forth.

Both the symbolic and connectionist branches of mainstream AI, from their earliest beginnings, are focused on direct imitation of the processes by which nature achieved intelligence in the human brain. This has been a very problematical task since reverse engineering the evolved intertwined complexity of neural circuity and cognitive functionally of the human brain is extremely complex. Some would say hopelessly difficult. Today’s artificial neural networks have been compared to worm brains in complexity and function. Mainstream AI has no roadmap to cross the gap of untold millions of years of neural-cognitive evolution that it took to achieve knowledge of the world in human brains.

In our last article we discussed how New Sapience has taken the contrarian approach; that nature’s way is not the only way. We studied knowledge itself as an information structure that could be directly realized in machines by engineered rather than natural processes, an approach philosopher John Haugeland described as Synthetic Intelligence.

The success of this approach has been unprecedented and our sapiens are already reliably exchanging ideas with human minds. This presents an interesting conundrum. How will theory of mind figure in human-sapiens interaction going forward when the snap back phenomenon inevitable with chatbots never comes?

Sapiens are synthetic intellects, not synthetic humans. They are not being designed to have the emotional states theory of mind will lead people to expect. It appears entirely possible to engineer behavioral routines that correspond to those states, and it would make interaction more natural. But is that a good idea or is it a slippery slope we don’t want to go down? If people are already willing to fall in love with something that they know is a mindless program, what kind of relationships will they form with one that clearly has a mind?